(note: this review kinda sorta assumes you’re familiar with Steven Pinker’s theories on the decline of violence. If you need a brief synopsis, watch this.)

Bear F. Braumoeller’s Only the Dead: The Persistence of War in the Modern Age is one of the most sophisticated rebuttals to Steven Pinker’s claims about the decline of violence, as presented in Better Angels and elsewhere. At its core, though, its argument is a variation on the same strategy every rebuttal to Pinker uses: Count something other than war deaths as the numerator or something other than world population as the denominator.

To his credit, the author reveals himself to be unusually self-aware of this issue:

One thing I’ve learned, though, both in paper presentations and in one-on-one discussions, is that if you think (prevalence of war death as a metric of violence) is the one that matters, I won’t have changed your mind by now, and I probably never will.

(The people whose minds he can’t change) want to understand how bad war is as a worldwide public health problem, whereas I want to understand the nature of war as a form of organized human behavior. De gustibus non est disputandum: There’s no point arguing about which one we should care about.

But I’m not sure Braumoeller realizes how problematic this admission is. The “war as a public health problem” team includes basically everyone he’s arguing against, including Pinker. He can claim to have rebutted Pinker only to the extent that he disputats the gustibus, because Pinker’s core empirical claim stands uncountered: A smaller fraction of the world’s population is suffering and dying in wars today than at any previous time in human history.

Nevertheless, this book’s analyses are worth exploring and I think they do point to some weaknesses in Pinker’s case. Braumoeller, like Pinker, believes that Richardson’s Law is roughly true: Wars of various sizes should be viewed as random events, and they follow a fat-tailed distribution in which there are many small wars as well as occasional huge wars. Both Pinker and Braumoeller recognize that this pattern makes testing statistically for a decline in the underlying “rate of war” difficult — if Richardson’s Law holds true, a decades-long stretch of relative peace could be a simple fluke, and the likelihood of a world-spanning war starting tomorrow could be just as high as it was in 1913 or 1938.

Pinker’s arguments are widely familiar at this point: He points to trends in global trade, the spread of democracy, the decline of militaristic ideology, and the growth of intergovernmental agreements as causes of peace; from these trends he concludes that the most likely reason we haven’t had a huge war in a long time is that civilization is genuinely less inclined to war than it used to be.

Braumoeller is much more pessimistic. He analyzes data concerning several processes that lead to war — namely the rates of initiation and escalation of armed conflict — and concludes that these rates don’t seem to have changed much over the past two centuries. From this analysis, he concludes that the only reason World War III hasn’t happened yet is that we’ve had an unusually long stretch of good luck.

There are a number of nits I could pick with Braumoeller — for example, the 19th century is widely recognized as an anomalously peaceful time period, so it might not be the best baseline to compare the 20th to — but for the sake of brevity I’ll focus on broad themes rather than methodology.

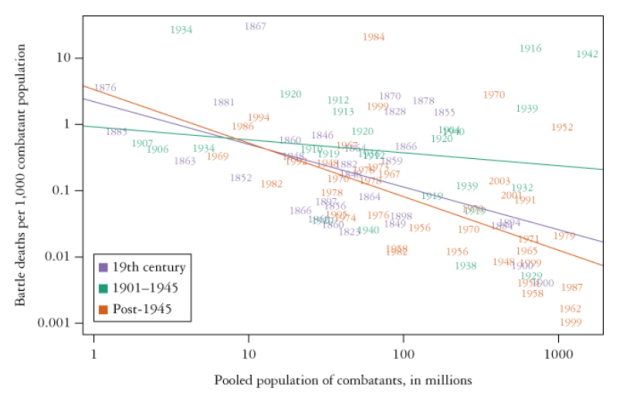

Two points of quasi-disagreement between Braumoeller and Pinker deserve special attention. First, assuming that the rates of conflict initiation and escalation haven’t changed, how is it then possible that the rate of war deaths have gone down? Braumoeller provides fairly convincing evidence that the main reason for the declining prevalence of war death is that larger countries send a smaller portion of their population to war (Dean Falk and Charles Hildebolt received some media coverage for a similar conclusion several years ago):

From this chart we can see that the relationship between a country’s population and its rate of death during war isn’t much different after 1945 than it was before 1901. It’s therefore plausible that the reason so few people die in war today isn’t because civilization has become less warlike; it’s because there are more of us on the planet, organized into larger political units than ever before.

I call this a “quasi-disagreement” because Pinker explicitly recognizes the organization of large political units as one of the drivers of peace throughout history. There’s a difference of emphasis, in that Pinker leans more heavily on other factors, especially when it comes to explaining the decline violence in the past few centuries. And I think it’s fair for Braumoeller to point out that “countries getting bigger” isn’t really something “Enlightenment values” should get credit for — it’s not one of the liberal, humanitarian trends Pinker likes to talk about most — but “scaling up civilization makes it more peaceful” is still very much in the Better Angels wheelhouse.

Braumoeller is also notably more pessimistic than Pinker about what he calls “international orders.” Pinker describes alliances like the United Nations, NATO, and the Concert of Europe as forces for peace; the growth in the scale and organization of such alliances in over the past several centuries makes war less likely. Braumoeller sees such alliances as double-edged swords: He argues that international orders reduce the probability of conflicts among their members, but increase the probability of conflicts between their members and the rest of the world.

To my mind, this argument falls a little flat. Braumoeller says that the existence of two competing international orders — such as NATO and the Warsaw Pact — tends to foster conflict. And it’s true that a large fraction of conflicts during the Cold War were proxy wars between the two orders. But the Cold War was also the Long Peace; the increase in conflict between the two orders was more than canceled out by the decrease in conflict within the two orders. If there are clear examples of cases where international orders increased violence, Braumoeller neglects to provide them.

Though this book clearly didn’t change my mind about whether violence has declined, it nevertheless gave me reason to reconsider how confident we can be that Enlightenment values are the best explanation for these trends, and that promoting those values is the best way to secure peace in the future — ironically, Only The Dead works better as a critique of Pinker’s more recent Enlightenment Now than of the book (Better Angels) it was written in response to. All in all, Pinker could use more critics like Braumoeller.