The 2019 college admissions scandal (sentencing underway) brought a wave of thinkpieces and cheeky tweets on the meritocracy, with the consistent message that America isn’t one. Two critics of meritocracy got a lot of name-checks: Michael Young, who invented the term in Rise of the Meritocracy, and Chris Hayes, whose more recent Twilight of the Elites: America After Meritocracy now seems shockingly prescient. Both warn that meritocratic ideology is dangerous, but the dangers they each point to are quite different.

What if meritocracy works too well?

Fun fact: The likes of Nineteen Eighty-Four and Brave New World were so influential in 1950s Britain that Michael Young’s publisher made him rewrite Rise of the Meritocracy, originally nonfiction, as a dystopian political satire. It’s fairly easy to discern the author’s actual point of view, so I’m not going to waste time by prefacing everything with “Young’s narrator says X, but what Young means is clearly Y”; I’ll simply review Young’s ideas.

Young wrote during an era that many consider the dawn of modern meritocracy, corresponding to the rise of the Tripartite System of Education in Britain and the Educational Testing Service in the United States. While the idea of meritocracy is in some sense far older, Young sets his sights specifically on the use of standardized testing to sort students into grade schools and colleges, and in turn the growth of a socioeconomic hierarchy based largely on educational credentials.

Unlike many critics of meritocracy, Young (a sociologist) accepted the consensus of mainstream social scientists: standardized tests do roughly what they’re supposed to do, in that they’re quite good at predicting how well students will do in school and correlate reasonably well with other measures of success and ability. Young had almost nothing to say about failure to achieve meritocracy in practice; rather, he was concerned with the unintended consequences of achieving meritocracy. Young took on a sort of steel man, arguing that even the purest, most successful version of meritocracy would have serious inegalitarian consequences.

- First, Young believed that values are plural. A society should not value only “merit” — which Young’s narrator defines simply as “I.Q. + Effort” — but also “kindliness and courage, imagination and sensitivity, sympathy and generosity.” Young saw the ultimate expression of this problem in tension between women’s desire to raise children and the relative lack of “merit” society sees in this activity, and his dystopia imagines that the most vigorous resistance to meritocracy will come from women’s dissatisfaction with the low value the system assigns to homemaking and childrearing (Young could perhaps be seen as a difference feminist in this regard.)

- Second, Young argued that “a good society should provide sinew for revolt as well as for power.” Meritocracy, perhaps even more so than other hierarchical ideologies, reassures the upper classes that they earned their higher status, and the lower class that they deserve their lowly station. Young waxes poetic on this point: “Authority cannot be humbled unless ordinary people, however much they have been rejected by the educational system, have the confidence to assert themselves against the mighty.”

- Finally, Young took genetics seriously. The type of ability that IQ tests measure is highly heritable (while the causes of IQ differences between different racial groups is controversial, there’s no serious scientific controversy over the fact that IQ differences within racial groups are largely genetic.) Thus, we should not expect that meritocracy, even tempered by affirmative action, will lead to social mobility in the long run. After a few generations, the upper classes will be dominated by people who pass their high IQs to their children, and likewise the lower classes will pass on their low IQs, ultimately recreating something strikingly like the hereditary aristocracy meritocracy was mean to abolish. This realization sets Young apart from most critics of meritocracy; as we will soon see, Hayes in particular seems blind to this issue.

What if so-called meritocracy doesn’t work?

Chris Hayes is clear about where he parts ways: “Michael Young’s prophecy got it wrong…in reality, our meritocracy failed not because it’s too meritocratic, but because it’s not very meritocratic at all.”

Hayes points to the Enron scandals, the failure of the FBI and CIA to prevent the 9/11 attacks, the unpopular war in Iraq, the government response to Hurricane Katrina, and the 2008 financial crisis, and argues that the elites in major institution of American society have failed. He blames what he calls the “Iron Law of Meritocracy”: The inequality produced by a meritocracy will ultimately subvert the system, by allowing those who initially succeed on meritocratic terms to rig the game’s future in favor of themselves and their friends and offspring. Indeed, the more important we make it to prove one’s merit, the more incentive there is to abuse the system¹.

The recent admissions scandals are an almost perfect example of this problem: Felicity Huffman is an award-winning actress who earned her success under meritocracy’s rules. She then tried to use the wealth she acquired from her successful career to secure unfair advantages for her daughter; specifically, to cheat on SAT, which is pretty much the exact definition of “subverting meritocracy.”

Huffman’s case is right on the nose, but it’s not clear how widespread the problem actually is. For every thirty-three parents who pay William Rick Singer to cheat their kids into college, there are presumably a hundred million or so who don’t. Every system is flawed to some extent; how are we to judge whether the admissions scandal is an exception or an exemplar of the typical workings of meritocracy?

Hayes’ litany of scandals — Enron, Iraq, Katrina — arguably have common thread of corrupted meritocracy, if you squint at them from just the right angle, but that’s far from the only pattern we could point to; for example, all these events were connected in various ways to a single presidential administration, led by a man who was notable in part for being a relic of a less meritocratic time. What if the problem with the awful aughts was not meritocracy at all, but simply George W. Bush?

Whether or not we’re in teh mood to blame Dubya, Hayes’ argument has a very general problem: When elites screw up, it’s difficult to say whether that means meritocracy is a failed system, or a system that sometimes fails. Perhaps we simply need to try meritocracy harder: End legacy admissions, reduce credentialism, send Felicity Huffman to jail, and so on.

Though Hayes never tackles this objection directly, he has two arguments that sort of address it. The first is that, during the era of meritocracy, social mobility in the United States has declined rather than increased. To Hayes, this proves that meritocracy fails more often than it succeeds and is ultimately a doomed project. Hayes can make this argument only because he assumes a functioning meritocracy should lead to social mobility. But Michael Young showed that this is not true; “merit” at least in the narrow sense measured by standardized tests, is largely genetic, and the reemergence of a hereditary ruling class might actually be evidence that meritocracy is “working” on its own terms.

“America seems broken.”

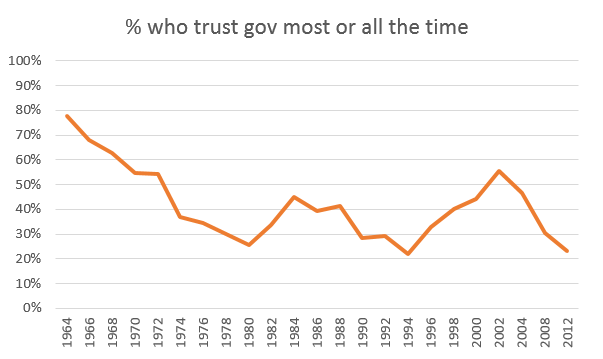

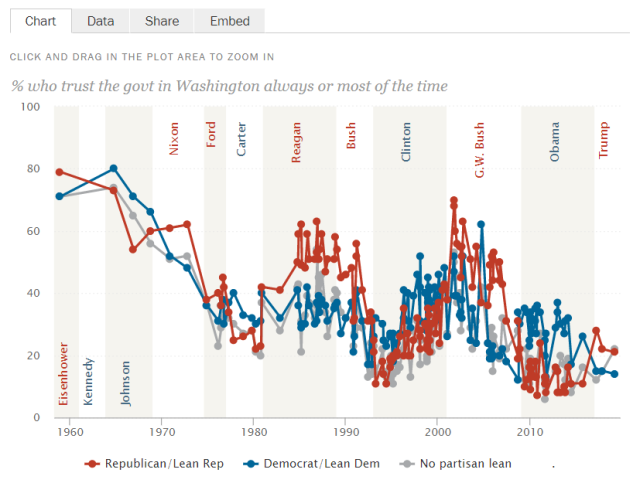

Hayes second argument — in some ways the heart of his story — is based on survey data that find a consistent, long-term decline in trust for American institutions; in the acknowledgements, he mentions that the book was originally inspired by a post on the topic Nate Silver wrote for FiveThirtyEight.com (most likely this one.) While the exact trends vary a bit depending on the source you use and the questions you ask, a pair of charts from the American National Election Survey and Pew Research show the general shape of things:

To Hayes, this decline is prima facie evidence that American institutions were in fact more trustworthy during the 1960s, when pollsters first started asking these questions, and have become less trustworthy over time. If you don’t believe that then, well, you’re probably one of the corrupt elites Americans so rightly distrust.

To Hayes, this decline is prima facie evidence that American institutions were in fact more trustworthy during the 1960s, when pollsters first started asking these questions, and have become less trustworthy over time. If you don’t believe that then, well, you’re probably one of the corrupt elites Americans so rightly distrust.

Either that, or a social scientist. The problem for Hayes is that decline in institutional trust — which has occurred in nearly all Western nations, not just the United States — is one of the most thoroughly studied questions in sociology and political science. If Hayes had done his homework, he would have learned that few researchers believe institutional corruption is the main reason trust has declined.

Nor have I done enough homework to give a full account of why trust has declined, unfortunately, and ultimately there is still quite a bit of disagreement among researchers as to the various causes. Some examples in the popular press: Marc Hetherington discusses the role of political polarization; Bill Bishop discusses the role of modernization (note that by 2017, the zeitgeist had changed and people were blaming declining trust on Trump and “fake news”, rather than elite failure and the 2008 financial crisis.)

The high-level common theme social scientists’ explanations share is that Western societies have grown more ethnically diverse, more politically polarized, and more individualistic. As a result of these changes, people feel less social cohesion and less trust in institutions — not just purported “meritocracies” like banks and universities, but also institutions that don’t even aspirationally reward merit, like churches and unions. Trust in other people — i.e. ordinary, non-elite individuals — has also declined. Hayes’ theory of meritocratic corruption doesn’t work very well as an explanation for these trends.

Nevertheless, I think major parts of Hayes’ argument can be salvaged.

First, even if we don’t buy Hayes’ declinist fable, neither does it seem that leadership of American institutions has gotten better during the era of meritocracy. Whether or not meritocracy is “working” — in the sense of sorting by merit — it doesn’t really seem to be delivering on its promise to make the world a better, fairer place (with one significant exception, in that many people consider improved opportunities for women and racial minorities to be a “meritocratic” reform.)

Second, one common finding in the public trust research is that economic inequality does seem to drive distrust. Despite its packaging, Twilight of the Elites is ultimately a book more about trust and inequality than meritocracy, and most of what it says on those topics hold up just fine.

What if meritocracy is just okay?

Scott Alexander of Slate Star Codex writes about meritocracy more optimistically, in a pair of posts suggesting that when people criticize “meritocracy”, what they really have a problem with is some combination of inequality and credentialism. He ultimately asks a very fair question: “(W)hat is the anti-meritocracy endgame?”

Young and Hayes both admit, more-or-less explicitly, that this is an extremely difficult question — neither wants to go back to when Yale students were largely the scions of wealthy families — and each tries to answer it in ways that reflect their slightly different takes on what the actual problem is.

Before I talk about their answers, I suggest a Google search on the phrase “loose meritocracy.” Your results may vary, but mine describes “loose” meritocracies in a variety of spheres: open source programming, professional wrestling, the Mughal Army, and posting pictures of hand-rolled blunts on Instagram. In each case, the writers are talking about formal or informal hierarchies where status and rewards are more or less based on performance in a certain area – though that performance is rarely “measured” in any explicit way. I submit that literally no one objects to “loose meritocracy” in this sense – that is, the practice of looking up to competent people and putting them in charge of important things.

Michael Young certainly did not object to this practice, nor was it what he had in mind when he invented the word “meritocracy.” Rather, he — followed by many other critics including Hayes — object to problems they believe arise when we try to make these loose hierarchies of accomplishment legible, by uniting them into a formal system or political ideology³. What the anti-meritocrats have in common is that they ask us to step back in various ways rom the ideal of legible meritocracy:

- Michael Young valued what is sometimes called a humanistic system of education; one that aims to enrich the lives and abilities of students in a wide variety of ways, regardless of how able the students are and whether that enrichment is profitable.

- Young also hinted that institutions may be more stable if we leave intact some vestiges of our seemingly natural, seemingly irrational inclination toward gerontocracy.

- Chris Hayes doesn’t seem concerned so much with tearing down the institutions of meritocracy as with tearing down its ideology; of maintaining deep, permanent dubiousness as to whether we’ve correctly measure the merit of the people at the top, and whether they deserve their status.

- Scott’s own anti-credentialism can also been seen as opposition to legible meritocracy – he would do away with college degrees as the singular measure of merit and replace them with evaluations of domain-specific competence. I don’t want to push this angle too far; Scott certainly values standardized testing — the ultimate tool of meritocratic legibility — much more highly than either of the critics mentioned above. Nevertheless, though he’s known for defending the validity IQ against denialists, he’s also quite skeptical that IQ reliably measures individual ability.

The anti-meritocracy endgame, then, is not to end meritocracy; it’s simply to keep meritocracy in its place, subject to perpetual skepticism, merely one organizing principle among many.

~

¹Note similar ideas in this economic model; assuming that cheating counts as a “high risk strategy.”

²Hayes puts a whole lot of weight on the advantages test preparation services provide for wealthier students, but those services don’t make nearly as much difference as he thinks they do.

³I don’t mean to suggest that legibility is always bad. As Fredrik DeBoer points out, “illegible” hierarchies are often worse. The SAT has a problem in that Felicity Huffman can pay to make her daughter’s scores higher than yours; the problem with “holistic” admissions is that Felicity Huffman can even more easily pay to make her daughter more interesting⁴ than you. Huffman’s daughter has her own IMDB page and you don’t, and unlike cheating on the SATs, that “holistic” advantage is perfectly legal.

⁴Nested footnote! You may argue that holistic admissions should place special value on the experiences of students who have experienced more adversity than Felicity Huffman’s daughter. But then you’re not really talking about “holistic” admissions anymore; you’re talking about affirmative action or adversity scores.